The Front

Around noon, I took the tram over to State Library Victoria. I arrived an hour before the tour that I scheduled so that I had time to observe the area. I walked halfway up the entrance stairs from the sidewalk and took a seat next to an old man on a bench. Sitting there, I took in my surroundings. The lawns were covered in people having picnics. The seagulls stood close by, waiting for any scrap of food. When anything dropped, a dozen birds flocked to it and fought each other. When there was nothing available, the seagulls would chase each other on their skinny, orange legs. They would dip their beaks low to the ground, ruffle their feathers, and run as fast as possible towards the tail feathers of another bird.

Looking away from the grass, I gazed towards the statues in the same clearing. The one directly in front of me was of Sir Redmond Barry—a prominent judge in the 1800’s and co-founder of the library. Holding a book in his left hand, his statue looked off toward a cluster of skyscrapers. Two ten inch spikes projected from the crown of his head to prevent birds from landing on him but it made him look like an old fashioned TV set or an alien.

The other two statues in the plaza were St. George and the dragon and Joan of Arc. These two looked over chessboards close to the entrance of the library. Joan guarded a game played by two young men in their 20’s while St. George slayed his foe above a chessboard where two men battled for a long time. They must have been locked in internal struggle because each move took minutes. They mostly sat there looking at the board.

I sat in the direct sun for 30 minutes, which is the longest that I had gone without putting on any sunscreen. Even after such a such short period, I could feel a sharp sensation in the tops of both of my forearms. I looked down. There was a blotchy red splash of color on both arms. The UV index in Australia is so high that you can get a serious burn in under an hour.

The Tour

I walked inside the main entrance and hooked to the left where groups met for the 90 minute “Dome to Catacomb” tour. Our guide was a tall, skinny man named Graham, who was a local of Melbourne and had been coming to the library since the 1950’s. His voice was a deep bass that was difficult to hear and I found myself frequently leaning in closer to be able to understand what he was saying.

Graham started by giving us a basic introduction to the history of the library. Founded in 1854, State Library Victoria is the third oldest public library in the world. In those times, you typically had to have special distinction or a letter of introduction from a noteworthy individual in order to get into a library. This library was different. The two requirements were that you had to be older than 14 and have clean hands. There were wash basins just inside the doors for this purpose. When the library was started, it was a library, museum, and gallery all under one roof. This changed over time with the museum and gallery each receiving their own buildings and the library taking over an entire city block. These days, the library contains over five million items available to the public, including books, records, newspapers, and more.

After a brief introduction to the history of the library, we crammed into an elevator with Graham and went up to the sixth floor of the dome. As we got off the lift, he casually mentioned, “I once got stuck on this lift with a tour group. The math doesn’t work out with how heavy people are these days.” He pointed out the weight limit printed near the buttons. I quickly stepped off the elevator, glancing over my shoulder.

The entirety of the dome came into view as we stepped up to the rail of the balcony. The domed room measured 35 meters high and looked like one of the libraries from Game of Thrones. The roof was made almost entirely of glass and let in large amounts of light thanks to the sunny climate. The area was a designated quite space, which left a church-like tranquility in the air. The acoustics were worthy of a cathedral with each slide of a chair or shuffle of papers sending a pinging reverberation that could be heard echoing even on the sixth floor. A warm sense of inspiration infused the bright dome.

After taking in the view, we followed Graham down the staircase until we stood on the floor above the seating area. Graham started talking about his own experience as a kid using the library in the 1950’s. At that time, only the seating area on the ground floor of the dome was open to the public. The balconies, where we stood for a vantage point from above, were locked and contained most of the books. In those days, he would have to go through the card catalog collection to find a book he was interested in seeing, and then he would bring that card up to the librarian. The librarian would climb a metal spiral staircase and walk up and down the balconies. Graham described how you could hear the librarian walk all the way around the dome, stop, and flick on a light. That was the cue that they might bring his book back soon. The whole process back then took about half an hour to get a requested book.

Graham then turned our attention to the seating arrangements in the dome. He pointed out that the tables were arranged in radiating spokes from the middle of the room where a platform rose up twice as high as the other seats. It was designed this way, according to Graham, so that a librarian could sit in the middle and look down each of the rows of seats to keep an eye on the patrons of the library. They called this person the “shusher” because they would shush anyone who was talking. They took this role so seriously that there was even a mirror placed on the platform so that the shusher could look at the clock on the wall and still be able to see behind them.

Moving on from the dome and sitting area, we were led to an oversized book that was encased in glass—”Birds of America” by John James Audubon. The book was printed on double elephant folio paper, which is the largest print size at just over two feet by three feet in size. Audubon used such large paper because each bird in the book was life size. Some birds had to be curved around the page to make them fit. The book is so rare that it is valued at around $10 million, making it the most valuable single item in that library.

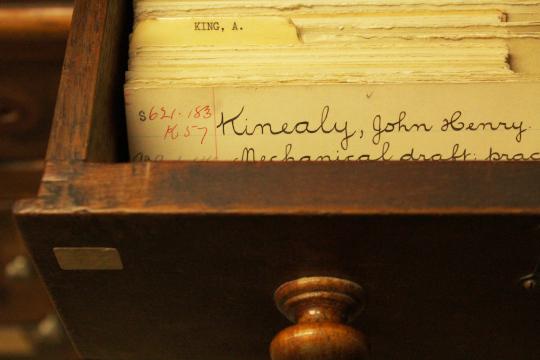

After completing the history of the dome, we crammed back into the tiny elevator and went down to the catacombs—a twisting maze of passages underneath the dome that held a substantial portion of the lesser used items in circulation. Row upon row of dormant knowledge waited for interaction. Even the walls were a storybook that told of countless renovations. Each hall had walls made of different kinds of brick. The mortar melted out in thick globs in some areas but was perfectly uniform in others. There were passages that had been sealed with brick and wooden doors that looked like they belonged in a castle. Behind one of these sat the remains of the card catalog collection. Dozens of wooden cabinets each contained drawers stuffed with hand written or typed entries. When I asked how many entries there were, Graham replied without hesitation that there were millions.

We walked back upstairs and proceeded through the rest of the library. We spent a great deal of time in the dome and catacombs, which were by far the most interesting, so the final couple rooms got little more than a brief glance and a story or two. As we were finishing the tour, we walked by the armor of the infamous Ned Kelly. With a wave of his hand, Graham dismissed the armor and said that he wouldn’t be talking about it.

Ned Kelly

Ned Kelly was an infamous Australian bandit who led a gang of thugs in the late 1800’s. They had committed many crimes but they were wanted in the end for killing several police. Australia had its roots as a penal colony for Britain which might explain why Kelly was able to find enough sympathizers to keep him from getting caught for two years. Eventually, the gang’s luck ran out and the police caught up with them in Glenrowan, a town northeast of Melbourne. Kelly lined his gang on the porch of an inn where they kept hostages and fired on the police as they approached. The fight raged through the night and ended with the entire gang’s death and the inn burning down. Kelly had managed to escape out the back door into the woods. When they sought him out, they were met with what they described as an apparition appearing from the fog. Every time they shot him, he seemed to be stunned only for a moment. As they got a better view of him, they realized that he had built himself a suit of armor made of scrap bits of iron. The metal suit had dented in many areas but prevented his death. One of the policemen realized he had no armor on his legs and used a shotgun to shoot the weak spot. They captured Kelly, who had dozens of wounds on his unarmored body parts, and brought him back to Melbourne for trial.

Despite all of his crimes, thousands of people called for his release. Sir Redmond Barry acted as his judge and quickly sentenced him to be hung for all the havoc he had caused. This would be one of Barry’s last acts, though, as he died only two weeks after Kelly. These days, the statue of Barry stands out front while the armor of Kelly sits in a glass case at the back of the library, like a trophy on display.

Graham’s refusal to talk about Kelly is a reflection of the division in Australian opinion. There are those that glorify Kelly as a Robin Hood character and say that he was a folk hero. There are others who describe him as a simple bandit that only brought death and chaos. These two sides argue whether he should have his armor on display at all. Regardless of the side one chooses, he is one of the Australians with the most books written about him. I don’t see him for much more than a rebel but I do find his story intriguing. His armored suit was undeniably clever and bears remarkable resemblance to the first Iron Man suit in the movies.

The End

While I was in Melbourne, I went to the library three separate times. It is the largest and most beautiful library that I have ever been to and there is always space for everyone despite it being the third busiest library in the world. It is alive to the same extent that most other libraries are dead. There is no doubt that, if given the chance, I would become one of the many for whom the library is a daily fixture.